Tens of thousands of citizens in person-centred approach

Ultimate form of smart mobility remains dot on horizon due to privacy risks

Urgency as it should be

Mass claim CUIC against virus scanner Avast launched

Your bank account: the shortcut to your private life (part 3)

27 Jun

PrivacyFirst Debate night

Your support allows us to exist. Donate now!

The Telltale Society

Registration Dutch Privacy Awards 2025 open!

Privacy First lawsuit against ANPR mass surveillance

Your bank account: the shortcut to your private life (part 2)

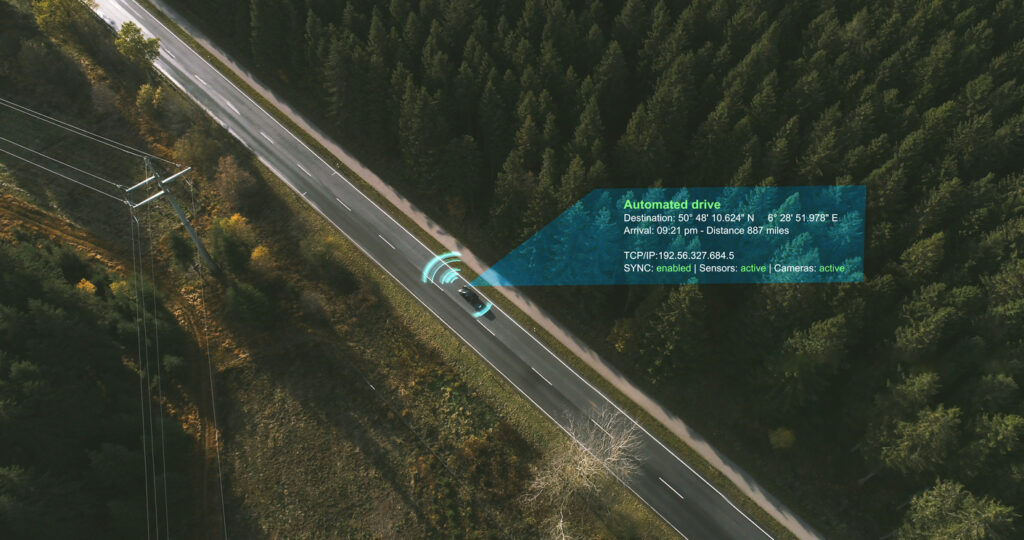

No 'smart traffic' without your vehicle and location data

Your bank account: the shortcut to your private life (part 1)

EHDS - and what did VWS do? (part 1)

National Privacy Conference 2024: bright spots and success stories

From smart doorbell to modern car, filming is almost always and everywhere

Winners Dutch Privacy Awards 2024 announced!

US car manufacturers violate privacy, mass tort claims dismissed

Debate night on the Internet of Things - report

Privacy First participation in DNB consultation

In the car from A to B, authorities surveillate with you

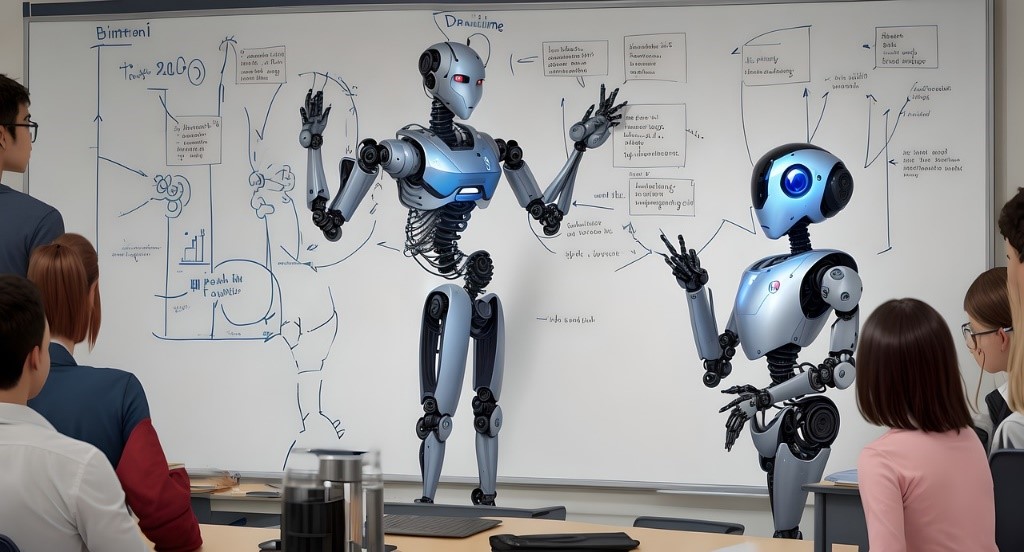

AI in education

Nominees Dutch Privacy Awards 2024 announced!

Kuipers' semantic quackery